Diabetes mellitus refers to a group of diseases that affect how your body uses blood sugar (glucose). Glucose is vital to your health because it’s an important source of energy for the cells that make up your muscles and tissues. It’s also your brain’s main source of fuel. If you have diabetes, no matter what type, it means you have too much glucose in your blood, although the causes may differ. Too much glucose can lead to serious health problems. Chronic diabetes conditions include type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes. Potentially reversible diabetes conditions include prediabetes — when your blood sugar levels are higher than normal, but not high enough to be classified as diabetes — and gestational diabetes, which occurs during pregnancy but may resolve after the baby is delivered.

Symptoms

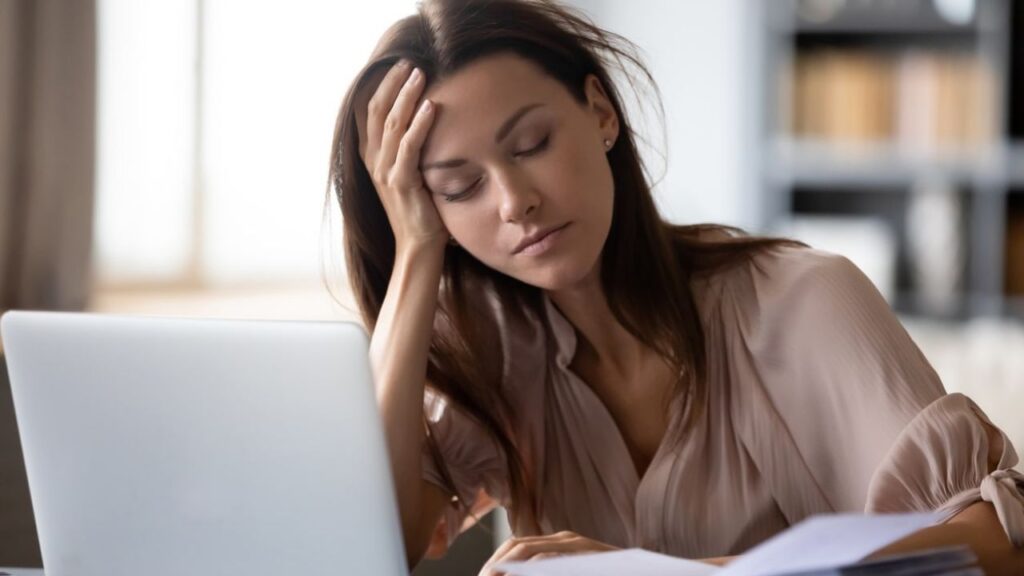

Diabetes symptoms vary depending on how much your blood sugar is elevated. Some people, especially those with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, may not experience symptoms initially. In type 1 diabetes, symptoms tend to come on quickly and be more severe.

Some of the signs and symptoms of type 1 and type 2 diabetes are:

- Increased thirst

- Frequent urination

- Extreme hunger

- Unexplained weight loss

- Presence of ketones in the urine

- Fatigue

- Irritability

- Blurred vision

- Slow-healing sores

- Frequent infections, such as gums or skin infections and vaginal infections

Causes

The exact cause of type 1 diabetes is unknown. What is known is that your immune system — which normally fights harmful bacteria or viruses — attacks and destroys your insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. This leaves you with little or no insulin. Instead of being transported into your cells, sugar builds up in your bloodstream. Type 1 is thought to be caused by a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental factors, though exactly what many of those factors are is still unclear.

In prediabetes — which can lead to type 2 diabetes — and in type 2 diabetes, your cells become resistant to the action of insulin, and your pancreas is unable to make enough insulin to overcome this resistance. Instead of moving into your cells where it’s needed for energy, sugar builds up in your bloodstream. Exactly why this happens is uncertain, although it’s believed that genetic and environmental factors play a role in the development of type 2 diabetes. Being overweight is strongly linked to the development of type 2 diabetes, but not everyone with type 2 is overweight. Another very common reason is inactivity. The less active you are, the greater your risk. Physical activity helps you control your weight, uses up glucose as energy and makes your cells more sensitive to insulin.

Having blood pressure over 140/90 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) is linked to an increased risk of type 2 diabetes. If you have low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), or “good,” cholesterol, your risk of type 2 diabetes is higher. Triglycerides are another type of fat carried in the blood. People with high levels of triglycerides have an increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

Complications

Long-term complications of diabetes develop gradually. The longer you have diabetes — and the less controlled your blood sugar — the higher the risk of complications. Eventually, diabetes complications may be disabling or even life-threatening. Possible complications include:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Nerve damage (neuropathy)

- Kidney damage (nephropathy)

- Eye damage (retinopathy), cataracts & glaucoma

- Foot damage

- Skin problems including bacterial and fungal infections.

- Hearing impairment

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Impotency

- Erectile dysfunction (men)

Diabetes and role of exercises

Diabetes and exercise go hand in hand, at least when it comes to managing your diabetes. Exercise can help you improve your blood sugar control, boost your overall fitness, and reduce your risk of heart disease and stroke. But diabetes and exercise pose unique challenges, too. To exercise safely, it’s crucial to track your blood sugar before, during and after physical activity. You’ll learn how your body responds to exercise, which can help you prevent potentially dangerous blood sugar fluctuations.

Before exercise: Check your blood sugar before your workout

Before jumping into a fitness program, get your doctor’s OK to exercise — especially if you’ve been inactive. Talk to your doctor about any activities you’re contemplating, the best time to exercise and the potential impact of medications on your blood sugar as you become more active.

For the best health benefits, experts recommend at least 150 minutes a week of moderately intense physical activities such as:

- Fast walking

- Lap swimming

- Bicycling

If you’re taking insulin or medications that can cause low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), test your blood sugar 30 minutes before exercising.

Consider these general guidelines relative to your blood sugar level — measured in milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) or millimoles per liter (mmol/L).

Lower than 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L). Your blood sugar may be too low to exercise safely. Eat a small snack containing 15 to 30 grams of carbohydrates, such as fruit juice, fruit, crackers or even glucose tablets before you begin your workout.

100 to 250 mg/dL (5.6 to 13.9 mmol/L). You’re good to go. For most people, this is a safe pre-exercise blood sugar range.

250 mg/dL (13.9 mmol/L) or higher. This is a caution zone — Your blood sugar may be too high to exercise safely. Before exercising, test your urine for ketones — substances made when your body breaks down fat for energy. The presence of ketones indicates that your body doesn’t have enough insulin to control your blood sugar.

If you exercise when you have a high level of ketones, you risk ketoacidosis — a serious complication of diabetes that needs immediate treatment. Instead, take measures to correct the high blood sugar levels and wait to exercise until your ketone test indicates an absence of ketones in your urine.

During exercise: Watch for symptoms of low blood sugar

During exercise, low blood sugar is sometimes a concern. If you’re planning a long workout, check your blood sugar every 30 minutes — especially if you’re trying a new activity or increasing the intensity or duration of your workout. Checking every half-hour or so lets you know if your blood sugar level is stable, rising or falling, and whether it’s safe to keep exercising. This may be difficult if you’re participating in outdoor activities or sports. However, this precaution is necessary until you know how your blood sugar responds to changes in your exercise habits.

Stop exercising if:

– Your blood sugar is 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) or lower

– You feel shaky, weak or confused

– Eat or drink something (with approximately 15 to 20 grams of fast- acting carbohydrate) to raise your blood sugar level, such as:

- Glucose tablets or gel (check the label to see how many grams of carbohydrate these contain)

- 1/2 cup (4 ounces/118 milliliters) of fruit juice

- 1/2 cup (4 ounces/118 milliliters) of regular (NON-diet) soft drink

- Hard candy, jelly beans or candy corn (check the label to see how many grams of carbohydrate these contain)

Recheck your blood sugar 15 minutes later. If it’s still too low, have another 15 gram carbohydrate serving and test again 15 minutes later. Repeat as needed until your blood sugar reaches at least 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L). If you haven’t finished your workout, you can continue once your blood sugar returns to a safe range.

After exercise: Check your blood sugar again

Check your blood sugar as soon as you finish exercising and again several times during the next few hours. Exercise draws on reserve sugar stored in your muscles and liver. As your body rebuilds these stores, it takes sugar from your blood. The more strenuous your workout, the longer your blood sugar will be affected. Low blood sugar is possible even four to eight hours after exercise. Having a snack with slower-acting carbohydrates, such as a granola, oats, nuts, seeds dried fruits or trail mix, after your workout can help prevent a drop in your blood sugar. If you do have low blood sugar after exercise, eat a small carbohydrate-containing snack, such as fruit, crackers or glucose tablets, or drink a half-cup (4 ounces/118 milliliters) of fruit juice. Exercise is beneficial to your health in many ways, but if you have diabetes, testing your blood sugar before, during and after exercise may be just as important as the exercise itself.

Strength training

Strength training when done correctly has been shown to provide a safe and effective way to control blood glucose, increase strength, and improve the quality of life in individuals with diabetes. Strength training (in the form of weight lifting) is also an effective form of exercise for the vast majority of diabetic patients. It helps improve muscle tone and in some cases increases muscle size. Larger muscles burn more calories even when you are resting, therefore regular resistance training can help lose fat and control blood glucose 24 hours a day. It may also help reduce the risk of heart disease. Before starting any weight lifting routine see your doctor as lifting weights for some diabetics may worsen their diabetic complications.

Caution!

DO NOT do strength training if you have type 1 diabetes and your blood glucose level is greater than 250mg/dl or if you have high levels of ketones in your urine. High urinary ketones means that your insulin is too low and your body is breaking down fats for fuel. Don’t exercise until you’ve got your glucose down near normal and your ketones down to just traces. And please, don’t do resistance training with either type of diabetes if your blood glucose is greater than 300mg/dl.

How hard to exercise

The intensity at which you should start exercising, depends on your physical condition, age and previous exercise background. What is light exercise to one individual, may be hard for another. Therefore your starting level will depend on your exercise background, physical status and the duration of the exercise to be performed. There are several ways to monitor how hard you are exercising. One is to work between 60 – 80% of your heart rate. For those people who are starting back into exercise after a very long time, levels of 40 – 60% may be recommended until fitness improves. Otherwise the best way is to go through complete health & fitness assessments for better safety and optimal results.

Strength training guidelines for people with diabetes

Number of sets and repetitions. 1-2 sets per exercise is a good starting point for you. Repetitions can be established in the same manner as you would for an individual without diabetes. Base your individual goals on your exercise tolerance. In general, use lower repetitions/higher resistance for strength and higher repetitions/lower resistance for endurance. Rest time between sets. Using 30-60 seconds for the rest period is appropriate in most situations. With greater intensity bouts a slightly longer (up to 2 minutes) rest period may be necessary. Frequency of strength training. Having strength train at least two days per week is appropriate in order to see beneficial results from the type of exercise.

Duration of your workout

If you are just starting or returning to exercise after a long time off you should begin by slowly building up to a target of around 30 – 60 minutes per exercise session. Always make sure that you do enough warm up for around 5 minutes, this includes stretching taking deep breaths. A good way to start back into physical activity is by increasing your general every day activity.

For example:

Taking the stairs instead of the elevator at the office.

Regular morning walks for 30 minutes at a brisk pace.

Clinical considerations regarding weight training for diabetics

Some considerations regarding exercise prescription involve lessening the risks involved with exercising people with diabetes. In cases where you have cardiovascular problems and high blood pressure, you need to consult your physician before progressing. Also, use lighter weights, as they will not increase blood pressure as much as the higher loads. It is also important to attempt to minimize the risk of you developing hypoglycemia (low blood glucose) during exercise. Regular meals such as eating 2 hours before exercise, having a light meal just before exercise, checking your blood glucose before and during exercising, and knowing the warning signs of hypoglycemia will help exercise tolerance. Knowing when to stop exercise and seek emergency care is a point that cannot be overstated. You should consult your dietitian on what foods are appropriate to eat before, during, and after workout. Also follow general exercise guidelines such as proper warming up and cool-down, safe footwear, adequate hydration, and avoid exercising in extreme conditions.

The DO’s regarding strength training.

- Try to get into a good routine by exercising at the same time each day whether this be in the morning or afternoon, evening or maybe midnight!

- Take special care of your feet. Make sure you wear comfortable shoes.

- Get a workout partner in the gymnasium. This will help motivate you and protect you in case an emergency situation should develop.

- Drink plenty of water and other fluids before, during and after activity. By the time you’re aware of being thirsty you’re already significantly dehydrated.

- Be sure to carry identification including diabetes medical identification.

- Forget “no pain, no gain” on this one. If something hurts or you feel too hard to do a particular exercise immediately stop that. It’s no fun to workout in pain and doing so risks injury.

- Forget intensity here. Focus on regularity. Slow and steady wins the race to fitness and better health for diabetics. Workout everyday with light workloads for best results.

Dr Saranjeet Singh

Fitness & Sports Medicine Specialist

Lucknow (UP), INDIA